In two days, the 40th anniversary of the shootings at Kent State University will occur. Forty years.

In May 1970 I was a 12-year old boy growing up about ten minutes from Kent State. Six years later, I was student there. And now I am an alumnus, having earned both my Bachelors and Masters degrees there. That doesn't make me any kind of expert on what happened on 5/4/70, but it does, hopefully, point out that the venue has been a large part of my life.

I still remember riding with my mom on the weekend that preceded the shootings. We were passing the National Guard Armory in Akron, where a line of trucks, troops and equipment were rolling down the highway. I asked my mom what this was all about. She replied "Oh, there's something going on at Kent State and the governor called the National Guard." And as usual, when my mom said something, it had a certain logical finality to it that made me just think, oh, okay. And that was that.

But then Monday May 4th came. And the tragedy of that day, as we know, ended up having far-reaching ramifications that vastly changed geopolitics, and, as many historians concluded, aided in ending the Vietnam War. As a black student colleague of The Washington Post writer Clarence Page stated, "Man, they're killing white kids now." Anti-war protests up to that point were considered communal sit-ins where the far-left fringes smoked dope & sang Joan Baez songs. After Kent, this stuff became serious. Now it was clear that your life could be in danger if you dared speak up...or show up. Which, given American's penchant for thumbing their noses at authority, had the effect of exponentialism. It made people angrier. And louder. And eventually, no longer at war in a far away jungle.

jungle.

But in my community it had a very different effect. Thi

s happened in our backyard, and many families had both Kent State students and National Guard members in them. Picture that dinner conversation. In neighborhoods and bars across the area, you would have violent arguments between people who had a child in college there, and another who had a Guardsmen as a son. Those Guardsmen were local kids too. It was, in effect, a Civil War scenario in northeast Ohio. And up until that point we were just middle-class middle-America. We weren't overly concerned with worldly matters. But what we became gravely concerned with was how our community was being torn apart - Kent State was not some kind of activist hotbed - it just happened to be the intersection point of history. And we had a real hard time accepting that.

Through the years, the University has had difficulties in adequately commemorating this event. For the first ten years, it was a head-in-sand mentality, almost as if the University refused to believe it occurred. Case in point - the parking lot where three of the four students died remained unchanged for years. It was as if the University was saying that having places for cars to park took precedence. They even tried to officially change the name of the University from 'Kent State' to just 'Kent'.

In May 1970 I was a 12-year old boy growing up about ten minutes from Kent State. Six years later, I was student there. And now I am an alumnus, having earned both my Bachelors and Masters degrees there. That doesn't make me any kind of expert on what happened on 5/4/70, but it does, hopefully, point out that the venue has been a large part of my life.

I still remember riding with my mom on the weekend that preceded the shootings. We were passing the National Guard Armory in Akron, where a line of trucks, troops and equipment were rolling down the highway. I asked my mom what this was all about. She replied "Oh, there's something going on at Kent State and the governor called the National Guard." And as usual, when my mom said something, it had a certain logical finality to it that made me just think, oh, okay. And that was that.

But then Monday May 4th came. And the tragedy of that day, as we know, ended up having far-reaching ramifications that vastly changed geopolitics, and, as many historians concluded, aided in ending the Vietnam War. As a black student colleague of The Washington Post writer Clarence Page stated, "Man, they're killing white kids now." Anti-war protests up to that point were considered communal sit-ins where the far-left fringes smoked dope & sang Joan Baez songs. After Kent, this stuff became serious. Now it was clear that your life could be in danger if you dared speak up...or show up. Which, given American's penchant for thumbing their noses at authority, had the effect of exponentialism. It made people angrier. And louder. And eventually, no longer at war in a far away

jungle.

jungle.But in my community it had a very different effect. Thi

s happened in our backyard, and many families had both Kent State students and National Guard members in them. Picture that dinner conversation. In neighborhoods and bars across the area, you would have violent arguments between people who had a child in college there, and another who had a Guardsmen as a son. Those Guardsmen were local kids too. It was, in effect, a Civil War scenario in northeast Ohio. And up until that point we were just middle-class middle-America. We weren't overly concerned with worldly matters. But what we became gravely concerned with was how our community was being torn apart - Kent State was not some kind of activist hotbed - it just happened to be the intersection point of history. And we had a real hard time accepting that.

Through the years, the University has had difficulties in adequately commemorating this event. For the first ten years, it was a head-in-sand mentality, almost as if the University refused to believe it occurred. Case in point - the parking lot where three of the four students died remained unchanged for years. It was as if the University was saying that having places for cars to park took precedence. They even tried to officially change the name of the University from 'Kent State' to just 'Kent'.

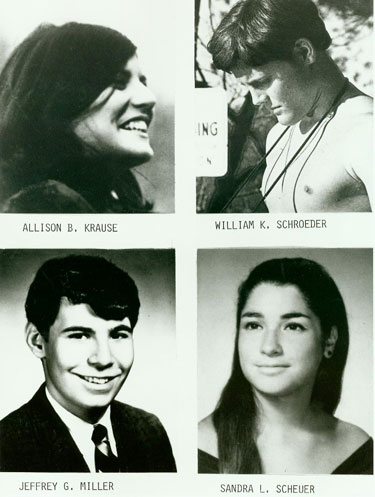

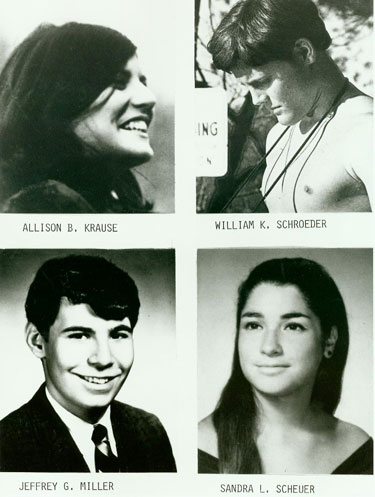

But as the years went on, and the historians wrote the accounts of the Vietnam War, Kent State was increasingly recognized as a pivotal point. It was when the war came home. It was then that the University realized that history occurred here, and it could not be denied. Today, the efforts put forth to recognize the events are, in my opinion, perfect. That Prentice Hall parking lot now had cordoned-off areas where Jeffrey Miller, Sandra Scheuer & Allison Krause died (see the picture to the right - that's Jeffrey Miller's spot where the 6 lanterns are under the pagoda roof). William Schroeder's felled spot is also cordoned off. There is a memorial to the east of Taylor Hall with four granite monoliths, and to put it in context, 58,226 flowers were planted around them - the number of U.S. deaths in Vietnam. T he pagoda where the Guard fired still stands. As does the metal sculpture next to Taylor Hall with a bullet hole in it.

he pagoda where the Guard fired still stands. As does the metal sculpture next to Taylor Hall with a bullet hole in it.

he pagoda where the Guard fired still stands. As does the metal sculpture next to Taylor Hall with a bullet hole in it.

he pagoda where the Guard fired still stands. As does the metal sculpture next to Taylor Hall with a bullet hole in it.What were the lessons of Kent State? Oh my goodness. Volumes have been written on that subject. Who was to blame? Ditto. And I am not going to get into that here. But I do have to say how it affected me. This is, after all, my blog. I spent a lot of time reading about this event. I have walked the site of the shootings countless times. I have even talked to some of the wounded students - and some of the Guardsmen. And in the final analysis I cannot fathom a situation that necessitated armed troops firing on unarmed students, killing four, wounding nine.

So my lesson was a pretty simple one. Just two words:

Question authority.

So my lesson was a pretty simple one. Just two words:

Question authority.

No comments:

Post a Comment